Peace by Pieces

At some point, leaders of Europe and North America are going to have to start discussing the future of European security. Until now, the focus has been on the war in Ukraine. But there are signs of a move towards a ceasefire and negotiations on a political settlement. Still, Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is only one of two conflicts affecting security in Europe; the other is between Russia and the West. It will be very difficult to solve one without addressing the other.

The last few major reforms of the international system have been after a war: in 1815, with the Congress of Vienna; 1919 with the Treaty of Versailles; and in 1945 with the founding of the United Nations. What can be expected this time?

There are many variables to consider. Firstly, ending the war in Ukraine in a way considered fair by key stakeholders will be an essential step for rebuilding European security. A core issue is security guarantees. How can countries, starting with Ukraine, feel assured that they will not be invaded again? How can both Russia and the West overcome a “security dilemma” in which steps to enhance national security on one side are regarded as a threat to national sovereignty on the other? Arms control and confidence-building measures will be vital, especially along a several thousand kilometre contact zone between NATO and Russia.

Reaffirming or renewing the fundamental principles of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) will be the bedrock of a future European security order. Otherwise, if there are no common rules, the foundations of any future arrangements will be weak.

Security will have to be considered in a broad context including energy security, environmental sustainability, and dealing with transnational threats and challenges such as organized crime, large-scale migration, terrorism, and cyber threats. It will also be vital to focus on human security, such as how to defend human rights and protect minorities. Furthermore, the future of security and cooperation in Europe will be affected by how states and peoples come to terms with rapid technological changes such as artificial intelligence. There should also be agreement on non-interference in cyber-space or underwater cables; all states should see the self-interest in not cutting the arteries of an interconnected world.

European security is not a self-contained ecosystem. It is affected by developments in other parts of the world, for example in the Middle East, the Arctic and China’s rising role in international security. Therefore, any discussions on the future of European security will have to factor in the continent’s relations with the rest of the world.

With so many issues, actors and variables to consider, where to begin? Since different countries and regions have different priorities and perspectives, a useful starting point would be to map out the wide range of political objectives that need to be considered.

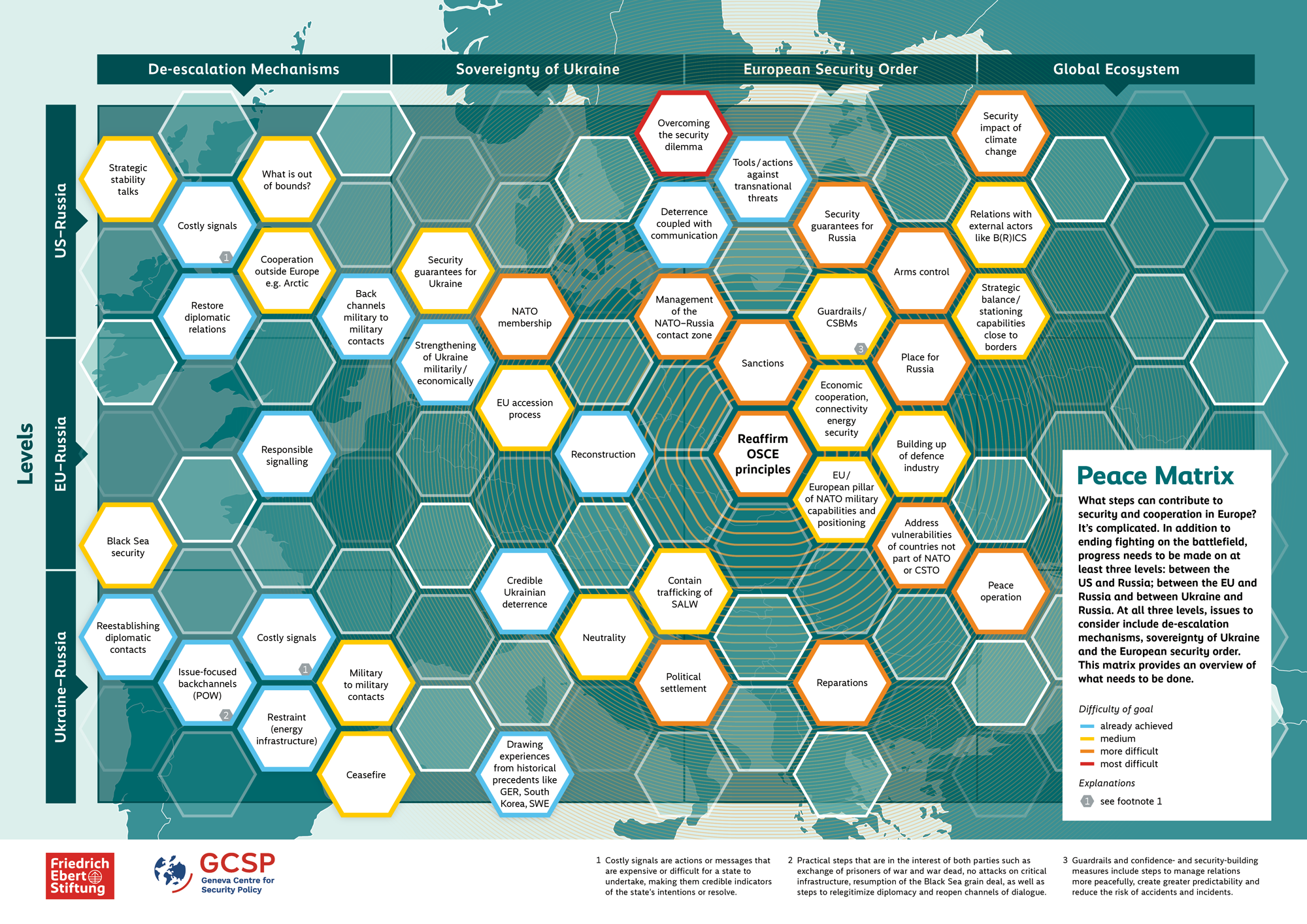

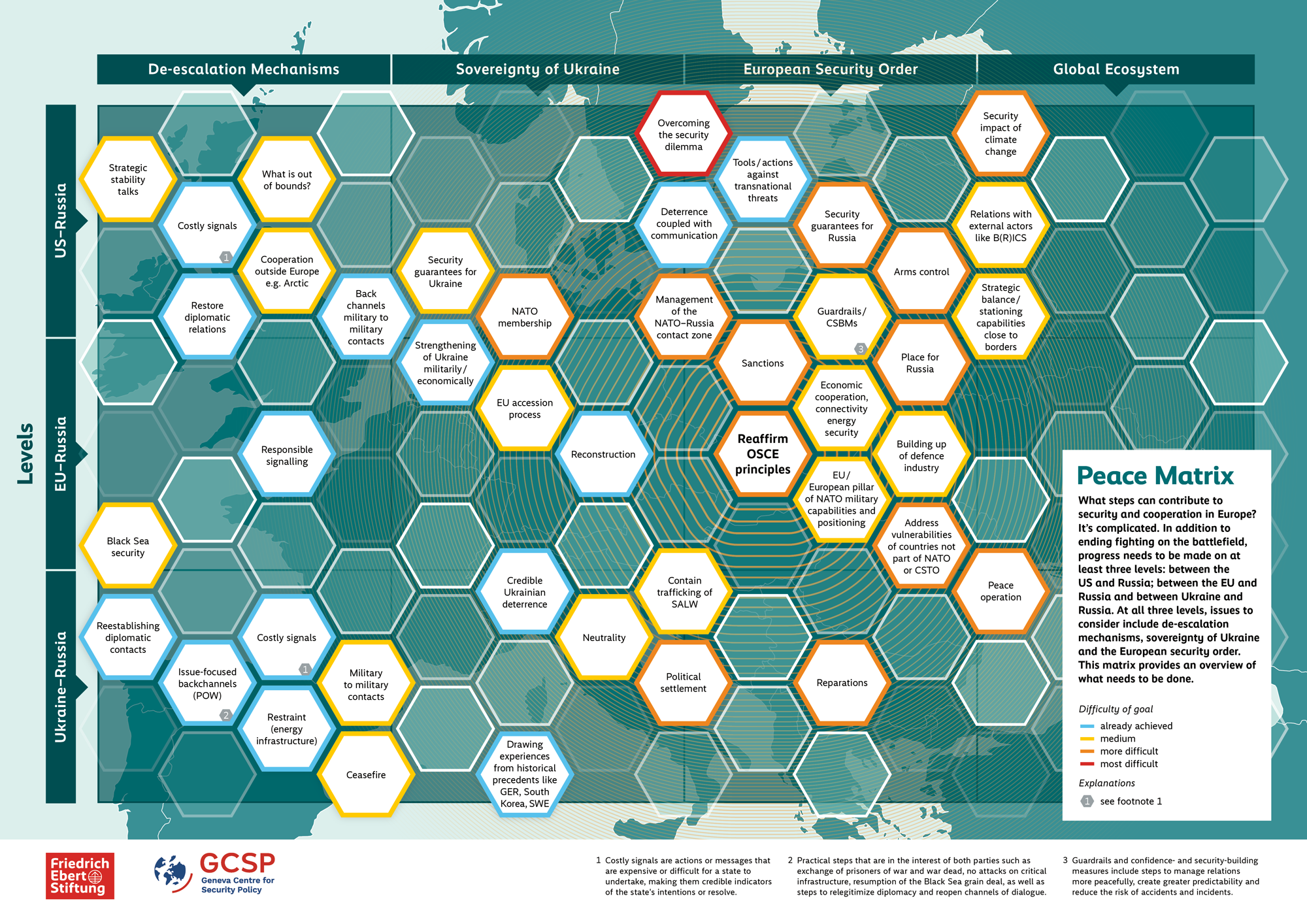

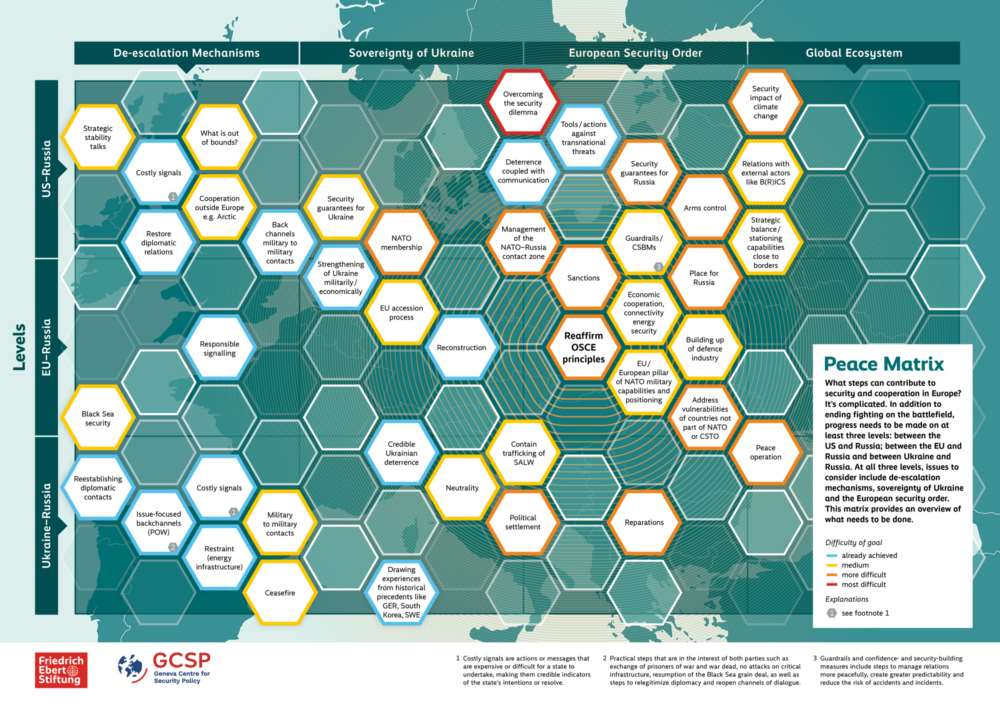

A first attempt has been made by the Geneva Centre for Security Policy together with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung as a result of a series of “conversations on the future of European security” that have been carried out with experts from Europe, North America, Ukraine and Russia over the past two years. This Peace Matrix shows the comprehensive and complex set of issues at stake.

The matrix illustrates that issues need to be considered at different levels, for example between Russia and the United States, between the EU and Russia, and between Ukraine and Russia. That suggests there is not only one table for mediators to be at; there will have to be different negotiation formats. The matrix also shows the diversity of objectives to be addressed from de-escalation mechanisms, to the sovereignty of Ukraine, and the broader issue of the future of European order.

It is neither necessary nor possible to do everything at once, nor is it essential to move sequentially from left to right. But everything needs to be on the table and considered in order to appreciate the magnitude of the task and to help policymakers set priorities.

Such a matrix could be an inspiration and starting point for a series of consultations on how to improve security and rebuild cooperation in Europe after the war in Ukraine. A useful precedent is the “Helsinki process” that took place between 1973 and 1975 resulting in the Helsinki Final Act that was signed fifty years ago on 1 August 1975. Switzerland, which played a key role as a bridge-builder back then, can play a similar role, not least when it chairs the OSCE in 2026.

It will take years to rebuild trust and security in Europe. The time to start preparing for the future is now.

Walter Kemp is Senior Strategy Advisor at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and author of “Security through Cooperation”.

Comments

* Your email address will not be published